Imagine kissing a stranger on stage in front of an audience of people. For many actors, this intimidating thought is another day at work.

Many of us have seen stories told in the theatre through acting, singing, and dancing. There is also a physical nature to acting as many plays show themes of romance. When you see Romeo and Juliet share a kiss on stage, have you ever wondered what work that led up to that moment from the real people playing those roles?

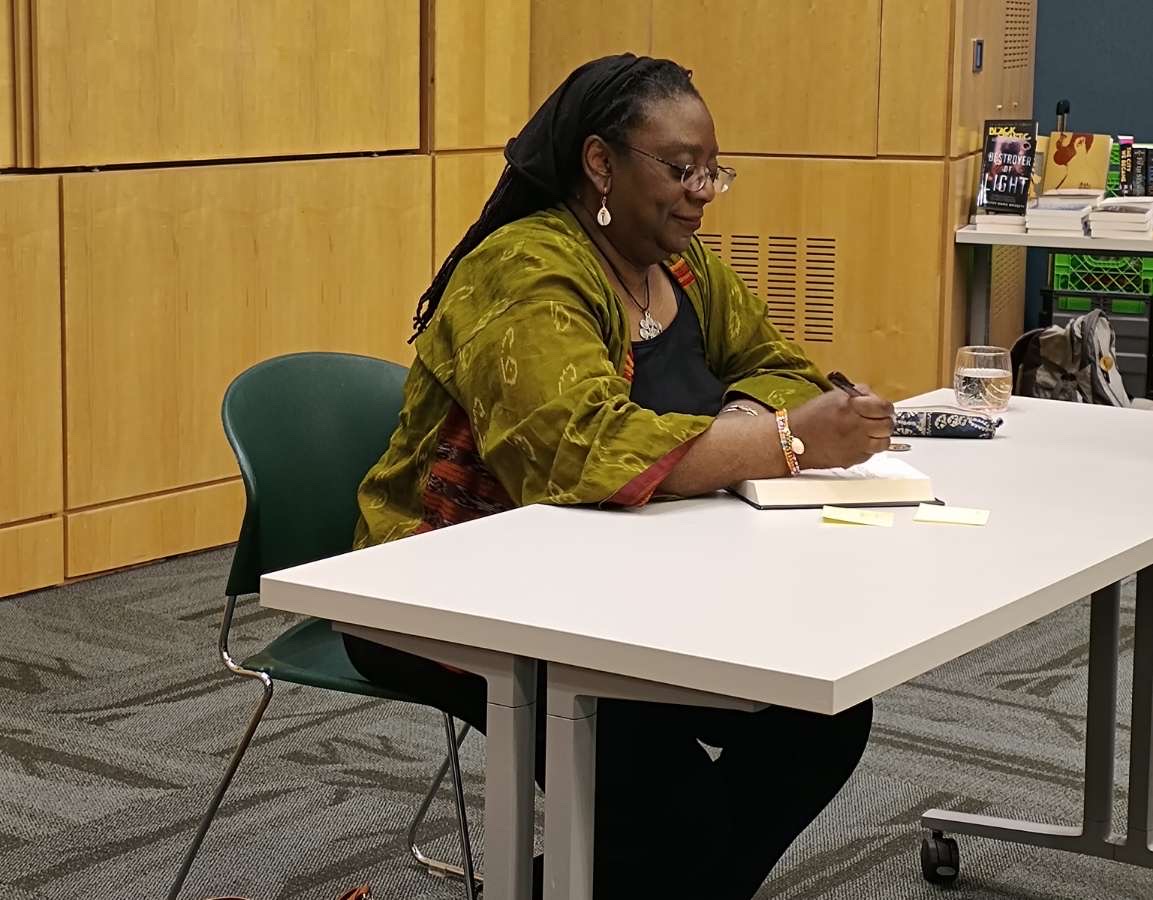

Intimacy director Jill Rittinger details her role in coordinating these moments.

“My role as the intimacy director for any production is to be an advocate for the actors and to be a liaison between the actors and production staff,” said Rittinger.

To show intimacy on stage, Rittinger choreographes scenes that can be recreated every performance, leaving nothing to chance. She is currently working of the play Proof at SUNY Brockport.

Actors Claudia Coonan and Jason Keirsbilck, playing the roles Catherine and Hal respectively, have been working with Rittinger.

“It’s hard sometimes to interact that way with a peer, I know we’re actors but still! I appreciated her respect for our boundaries and comfort levels,” said Coonan.

Claudia is a dance major and is able to learn choreography very quickly. Rittinger describes intimacy as less of a dance and more like fight choreography.

“Fight choreography and intimacy direction are two sides of the same consent forward coin… you wouldn’t just hand someone a sword and say ‘do a sword fight,’” Rittinger said.

She explains there must be parameters in place for both intimacy and fight choreography to be safe. Showing intimacy on stage is not just ornamental to give the audience something else to look at. It propels the story and reveals more about the characters.

While the intimate scenes in Proof are not intense, they give us a new understanding of who these people are.

“Proof feels like there is a lot at stake for Catherine’s character, there are so many reasons for Catherine to be guarded,” Rittinger said.

This character showing a hesitation reveals a new layer to the character while raising the stakes of the scene. Raised stakes are what makes an audience care about the scene. Characters always have an objective, something that they want. Nobody opens their mouth to speak unless they want something and that something that they want needs to matter for an audience to be invested. Rittinger also reiterates the importance of communication between scene partners. She said that to have a successful intimacy rehearsal the actors should “check in and see how each other are doing not just about the show but about life.”

Other tips she gave were to advocate for yourself and push back from the culture of urgency that is so prevalent in the theatre due to the impending deadlines. In the performing industry there is an idea that if an actor is not willing to do something, there are ten more actors waiting outside the theatre who are. So after working so hard to get cast, many actors don’t want to be perceived as difficult to work with and will not advocate for themselves when they are in an uncomfortable situation.

This is where Rittinger comes in as an unbiased third party to advocate on behalf of the actors. To see these scenes come to life with Rittinger’s choreography, the play Proof will be performed for two weekends at SUNY Brockport in Tower Fine Arts, February 23-25 and February 29 – March 2 on the main stage.